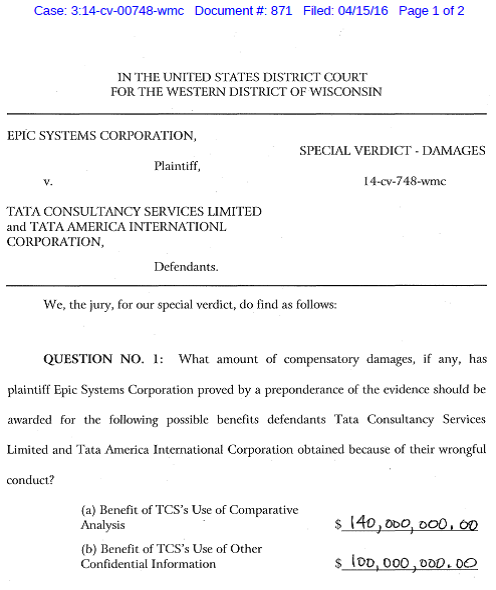

This is the third in a multi-part discussion [first part] [second part] about whether and when to cut-off damages for trade secret misappropriation. Similar posts on LinkedIn at [first], [second] and [third].

Guidance from the courts on these questions is not always consistent and depending upon the jurisdiction may not exist. This makes it hard to predict in a particular matter the length of time that will be allowed for recovery of trade secret damages.

A possible solution, one which is well-grounded in UTSA principles and related commentary, is extending the damages accounting period for as long as necessary to eliminate the unfair commercial advantage gained from actionable misappropriation. See Uniform Trade Secret Act (UTSA), § 3 cmt. (“Like injunctive relief, a monetary recovery for trade secret misappropriation is appropriate only for the period in which information is entitled to protection as a trade secret, plus the additional period, if any, in which a misappropriator retains an advantage over good faith competitors because of misappropriation.”).

Our first installment explained that the damages accounting period may extend beyond the time a trade secret is no longer protected because it has lost its secrecy.* Our second installment acknowledged that there are circumstances where damages end before the loss of secrecy. Why? Because the end of the commercial advantage period — the end of the time necessary to deprive the defendant of an unfair commercial advantage that is attributable to misappropriation – occurs before the trade secret loses its secrecy.

This installment addresses the use of the so-called “head start” rule as a temporal limitation on damages and flags different interpretations of the rule that may cause confusion or misunderstanding about the proper duration of a damages award. The many and varied head start concepts may compel a court to limit or expand damages in a manner that is inconsistent with the core principle of eliminating unfair commercial advantage. Continue Reading Unfair Head Start and Trade Secret Damages